Integrity Scales Better Than Deception

- Eric Boromisa

- 2 days ago

- 4 min read

Updated: 9 hours ago

In a transparent, hyperconnected market, deceptive business models don’t quietly fail—they unravel in public. What once passed as clever positioning or aggressive optimization now leaves a trail of evidence: internal emails, product inconsistencies, regulatory filings, and user screenshots that circulate faster than any official response.

Integrity isn’t a moral flourish added after success. It’s a structural property of businesses that intend to survive scrutiny at scale.

What follows isn’t a list of villains. It’s a pattern.

1. Consumers Eventually See the Full Picture

Modern consumers don’t need perfect information; they need enough signal to notice when claims and reality diverge. When pricing, performance, or values are misrepresented, the gap becomes visible through reviews, reporting, and peer networks long before a company can correct the narrative.

Example: Volkswagen (Dieselgate)

Volkswagen marketed its diesel vehicles as environmentally friendly while secretly installing software that detected emissions tests and altered engine behavior to pass them. In real-world driving, emissions far exceeded legal limits. When regulators uncovered the scheme, Volkswagen faced recalls, executive resignations, criminal investigations, and more than $30 billion in penalties and remediation costs. More importantly, the company lost credibility with customers who believed they were making responsible choices.

Why it was damaging: The issue wasn’t just cheating tests—it was the deliberate contradiction between brand promise and product reality.

2. Deception Amplifies Regulatory Risk

Regulators rarely punish ambition. They punish misrepresentation. When a company crosses from optimism into false claims, oversight shifts from routine to adversarial, and outcomes become difficult to contain.

Example: Theranos

Theranos claimed its technology could run hundreds of blood tests from a single finger prick. In reality, the devices didn’t work as described, and most tests were run on traditional machines while results were misrepresented. Investigations revealed systematic deception of investors, patients, and regulators. The company collapsed, and its founder, Elizabeth Holmes, was convicted of fraud and sentenced to prison.

Why it was damaging: Health claims carry real-world consequences. False confidence put patients at risk and permanently damaged trust in adjacent health-tech startups.

3. Leadership Behavior Becomes Brand Reality

In practice, corporate culture and executive conduct are inseparable from brand perception. Once issues surface, nuance disappears, and leadership becomes the focal point for accountability.

Example: Uber

Uber faced sustained criticism for workplace culture, including reports of harassment, retaliation, and ethical blind spots. These weren’t isolated incidents but systemic failures that reflected leadership priorities. Public pressure and internal instability eventually led to the resignation of CEO Travis Kalanick and years of restructuring to rebuild trust with employees, regulators, and the public.

Why it was damaging: Growth masked internal risk until the brand itself became synonymous with dysfunction.

4. Trust Gaps Create Competitors

When users feel instability or misalignment, they don’t need a perfect alternative—they need a credible exit. Deceptive or chaotic behavior creates space for competitors to position around clarity and restraint.

Example: X and the rise of Bluesky

After Twitter was rebranded as X, users experienced abrupt changes in governance, content moderation, and brand identity. Policies shifted frequently, enforcement appeared inconsistent, and the platform’s direction became harder to interpret. Bluesky, an independent company that originated years earlier as a Twitter research project, attracted users looking for a more stable and transparent social environment. This wasn’t a technical migration but a behavioral one.

Why it was damaging: Brand volatility made users question whether staying required constant justification.

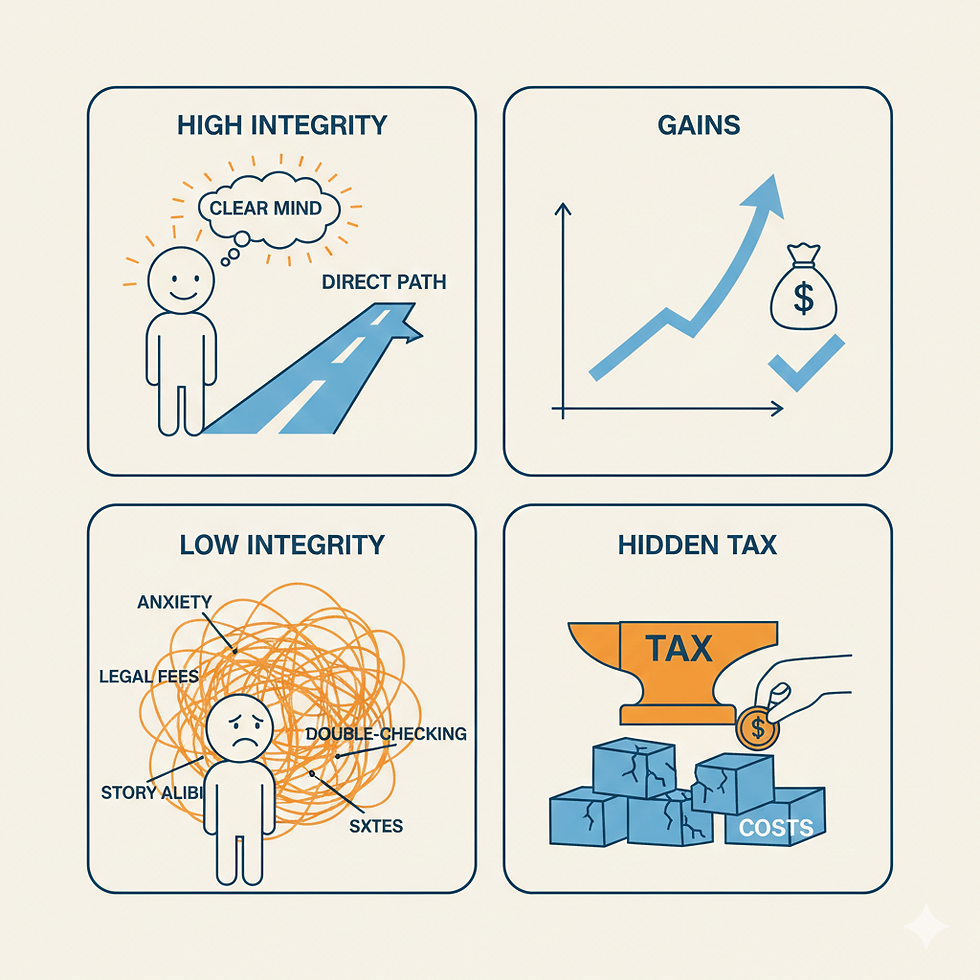

5. Crisis Management Is a Hidden Tax

Once deception becomes public, resources shift from building to defending. Legal fees rise, PR messaging multiplies, and leadership attention fragments.

Example: Wells Fargo

To meet aggressive sales targets, employees opened millions of unauthorized customer accounts. When exposed, the bank paid over $3 billion in fines, replaced leadership, and spent years attempting to rebuild customer trust. The financial penalties were severe, but the reputational damage proved longer lasting.

Why it was damaging: Internal incentives rewarded behavior that directly violated customer trust.

6. Talent Avoids Reputational Debt

Top performers evaluate risk beyond compensation. They consider whether association with a company will require future explanation.

Example: Enron

Enron was once viewed as an elite employer known for innovation. After its accounting fraud surfaced, the company collapsed, and former employees faced professional stigma simply due to association. The brand became shorthand for systemic deception.

Why it was damaging: Reputation followed people, not just the organization.

The Bottom Line

Integrity scales because it reduces friction across every interface a company has with the world: customers, regulators, employees, and partners. It lowers surprise risk, stabilizes decision-making, and allows leaders to focus on building durable systems instead of managing fallout. This isn’t about ethics as branding. It’s about alignment between what a company says, what it does, and what it can defend under scrutiny.

If this resonates, explore more of my writing at Numbers & Letters, or reach out for a consultation to examine incentives, trust, and long-term risk in your organization.

Disclaimer/Full Disclosure (You made it!): This blog post was generated with the assistance of AI, with N&L human oversight ensuring accuracy and insight. The thoughts and opinions expressed are our own.

Comments